Arrowroot and nostalgia: Is the Golden Age ever truly over?

Published in Doof Magazine, 2021

My 嫲嫲* tends to oversalt. This was a harried murmur, tossed sparingly and in between dinner times while she worked up a sweat in the back. She didn’t allow anyone else into the cramped kitchenette of her flat, relegating the rest of us to spooning out rice (exactly half-scoop,) and ladling the 上湯* into bowls. No one said a word when she’d arrange four platters—cubed ham and tofu bits, pork chops swimming in onion and brown gravy, chinese greens, and strangely enough, braised duck breast with orange. No one questioned it. My mother would watch with reproachful eyes as we emptied our bowls and polished off the sodium with a saltier soup to boot, often winter melon and salted egg.

While the adults congregated around the dining table peeling mandarins, my sister and I would sit on the opposing arms of the brown chaise; not unlike the rusted guardian lions that hovered over the doors of shrines. 嫲嫲 peeled pistachios like they were a secret. She’d deposit them into the fleshy centre of our palms—and I'd hold them for minutes, before eating them slowly haloed in the flare of red headlights on the drive home. The warmth of it would slosh for hours afterwards in my belly.

my grandmother in the 70s

I’m lucky to favour 嫲嫲. I’ve pored over photos of her in her youth, sometimes with a fur-trimmed coat, or large sunglasses paired with coiffed hair. I have the same creased, pillowy cheekbones and lips that jut outwards, a perpetual quasi-pout. On her, the effect is one that is elegant, esteemed, whereas I tend to look jaded.

Later when she derailed a little with age and my grandfather’s passing, I thought I hated her. I scorned the features I latched onto as a badge of pride in my younger years, hated the proudness of her chin, the strength of her nose. The handful of times I recalled her whispering epithets into my hair, forgive him, forgive your father, he loves you, your father loves you and your sisters, forgive him. Each line she’d smooth over with her hands, lined and speckled with the fat glint of her one karat wedding band —a measure beyond preposterous in her time of pre-boom Hong Kong. She’d knead the words deeper until they were half-submerged in my chest, and no amount of time would allow me to fish them out from where they had sunk.

Once, when I was fifteen, she left for the mainland without a word. When she returned, it was six months later, when the state of my parents’ marriage quietly wilted away. Explanation for either offense was not given.

Each time I return to Hong Kong, I am thunderstruck by how she has managed to work around her senility. Sidestepping, treading through old age, making it hers. The sagging flesh and sunkenness around her brows had only enhanced the shrewdness of her eyes. I see the grooves around those eyes dimple like twinset stars when she proffers me food, sinking a crisply folded note into my hand. I can never manage to stop myself from taking it.

Perhaps it is the fate of a child of the century—as my mother had always put it—squirming, canting for something we had very little idea about. We keened for the glory days enshrined in the splendour of old-time finery, yet remade familiar in the fabled noir aesthetics that the West laved praise onto. I am no exception. I put on Teresa Teng; an attempt to weasel my mother and grandparents for nuggets of information to authenticate the way I conducted myself in proximity to them. Did you listen to this? Was Hong Kong like this, in the 80s?

I liked to think in my rejoicing there was nuance, a deeper pursuit of connection that went beyond what I had known. But really, I am clinging on to a mirage-like effigy.

The past is slippery, never-stale.

There’s a saying that people in Shanghai think that they are superior to people from Beijing, simply because they’re from Shanghai.

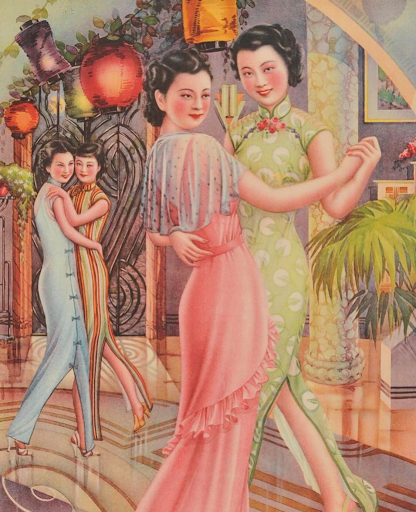

The old-Shanghai grandeur, in particular, is one that I’ve never been able to shed. I’m proud of my Shanghainese roots in the same way one preens over a particularly prized coat, or a beloved pair of shoes. I adorn myself in all of its crevices—the food is bright, delicately arranged, and the women are reputed to be the most beautiful across China. To me, they are portrayed in the same way: silken-white, with pops of colour that cut across an otherwise unassuming slate. In the high arch of the brows, the rosebud mouth, the perfect prick of rouge on either cheek.

On sweaty days, I’d nose in my grandmother’s dressers for cure-all Florida Spray. Made by the eponymous Two Girls Brand, it was the first cosmetic vendor that capitalised on the adrift market for perfumed cosmetics geared towards the Cantonese. Often, I would run my fingers over the smiling women, whose likeness I pivoted towards.

two girls florida spray design

Perhaps Anna May Wong was the first to export this illusion to Hollywood: courtesans, temptresses, dragon ladies, the likes. Careening into the golden age of cinema with a tawdry amount of pearls and the skin off her back to make a lasting impression. There are too many thinkpieces touting the shortcomings of her career; too few that simply revel at the grace with which she even got a foot in the draw-door to begin with.

I bought a dress today because the model sheathed in it had hair like Anna’s. Two semi-crescent plaits, which looped at the back against the trademark blunted bangs. It contrasted nicely with the collar of the purple dress, a helmet of hefted hair. I seized at the sight of it and that was the end of that. I didn’t think any more of it.

There’s a saying that people in Shanghai think that they are superior to people from Beijing, simply because they’re from Shanghai. There’s also a saying that people from Hong Kong think that they’re better than people from Shanghai, and from Beijing, simply because they’re not from either.

The superciliousness of Hong Kongers comes from decades of practice from mimicking its colonial counterpart. I know this to be true. I round each word from my mouth, pronounce the ‘th’s’ and ‘f’s in English without getting them confused. “Think of the people in China,” my mother would throw around loftily, and I’d conjure up images of ruddy children across the border, amusing themselves with silt and plants in thick Mandarin, in brick and mortar houses. Never mind that Shanghai and Shenzhen, which was the closest city adjacent to HKSAR borders, boasted similar skyscrapers and an outcropping population to boot. It was still a pale imitation at best of what my home had to offer, I would think, a little cruelly. It lacked the gravitas of the fragrant harbour, the effusive swirl of neon, the noir.

Photography by Greg Girard

Now I see beyond the veil. Beyond the ham-fisted grip of the government, beyond the betrayal of 嫲嫲, beyond my own breathtaking performance of identity. And still I cling to them: the figures and compositions half-real, half envisioned, that have been salvaged from the scraps of my life. I am clinging to the bust of painted ladies, my grandmother, my homes and the places I have laid to rest. Extolling them, amplifying where I see fit, donning the rose-tinted lenses when I gaze at looming horizons, on the brink of collapse. These fixtures are flawed yet I ruminate on them all the same.

Must we be tasked to make meaning of bygone things?

Do those who have wronged and been penalised for the crime of not doing and being more when they should have been stripped of their titling, discarded to the side?

There is something to be said about the past, in all its unevenness. We can still make a home out of it. We can cherish its asymmetries and find comfort in sieving through our memories, wantonly, selfishly.

Can’t we be beautiful? Don’t we owe it to ourselves to find beauty in the past, without a preamble? Without a debt?

My 嫲嫲 says;

“係噉先, Hai gum lah*.” — let bygones be bygones. Let’s turn our faces inwards.

To the past, a toast. That's it for now; that's all for now.

Index

上湯 — light broth that accompanies start/end of a Cantonese meal

嫲嫲 — grandmother on your father’s side

係噉先 — It is what it is, let us leave it for now